Click a section to expand it

History

The 1700s

Before the turn of the nineteenth century, the tything of (West) Leigh was made up of a scattered settlement, relying on Havant Thicket, a former part of the Forest of Bere, for its survival. This settlement around Leigh House dates back to the Medieval period, if not earlier. The first mention of a substantial house on the site, or very close to the site of Leigh House, dates to 1767, when on 20th April of that year, Captain Charles Webber R.N., purchased for £340 the ‘reversionary rights’ to a messuage, barn, and gateroom, together with nine acres of land, from Francis Higgins of Middlesex. Higgins was a butcher and had inherited the property on the death of his great-uncle George Higgins in that year. It is highly probable it was the same building that Robert Higgins was paying tax on for on three hearths in the 1665 Hearth Tax for the tything of Leigh.

Charles Webber, who in his naval career had reached the rank of Rear-Admiral, died 23rd May 1783, leaving a widow and five children who were all earlier baptised at Havant. In his will Webber left the small estate at Leigh, along with other land in West Sussex, to his wife Anne. It appears that very soon after his death the property passed to Samuel Harrison, who is recorded in certain records as ‘of Chichester’. A document which is sadly undated but certainly before 1792 refers to ‘the house newly erected by Samuel Harrison.’ This seems to confirm that Harrison had built the house that, after structural alterations by later owners, became to be known as the first Leigh House. A map dated between 1792 and 1800 clearly shows the house and other buildings, including the walled garden, stable block, coach-house, bothy, and the land held by various freeholders and copyholders around Leigh House. Apart from the house, most of Harrison’s other buildings survive, all built in a mellow yellow brick, popular at this time.

It must be remembered that most of the land at Leigh at this time was in the hands of the Bishop of Winchester, who granted the lease of the Manor of Havant to a succession of Havant worthies. These included Richard Cotton of Warblington Castle (in 1553) and later the Moody family. In April 1784 a new lease was granted to Richard Bingham Newland, who as Lord of the Manor began to dispose of parts of the Manor. In 1812 Newland conveyed the Manor of Havant to his brother-in-law William Garrett, who had acquired the Leigh estate in 1800.

From 1792, when Harrison ‘surrendered’ Leigh House to Captain Thomas Lennox Frederick R.N. (1750-1800), the development of the property becomes somewhat clearer. Captain Frederick was the son of Sir Charles Frederick, the Surveyor-General of Ordnance and a cousin of Admiral Sir John Frederick Bt. Frederick’s successful naval career included serving as a captain under Lord Hood at Toulon and Corsica in1792 and serving under Sir John Jervis and Nelson at the battle of Cape St. Vincent in 1797.

1800 - 1810

By 1800 Frederick held 20 acres of land around Leigh House, made up of further copyhold land under the manor of Havant. The largest landholder in the vicinity was Joseph Franklin of Qualletts Grove, Horndean, who held the farm close to Leigh House and over 220 acres of freehold land surrounding Frederick’s holdings – land that would eventually become part of the Leigh Park Estate.

It would appear that Frederick let the property at times; prior to his death in 1800 the house was occupied by his tenant John Allan. After the death of Frederick, who by this time had reached the rank of Rear-Admiral, his widow Anne, who was left Leigh House in the will of her late husband, sold the house and the land surrounding it to William Garrett (1762-1831) for the sum of £480. In 1802 Garrett had the house substantially rebuilt, employing the Southampton architect John Kent. By 1807 Garrett had acquired all of Franklin’s land, reputedly for the large sum of £4,600, and over the next few years acquired further copyhold land in the area turning the Leigh estate into one of the biggest in the neighbourhood.

Garrett came from a well-known Portsmouth family; his father was a Portsmouth brewer and owner of the Belmont Estate at Bedhampton, while his brother Vice Admiral Henry Garrett was Governor of the Military Hospital at Haslar. Another brother, George, who was knighted in 1820, inherited the family brewing business. William Garrett, together with his father Daniel, formed the ‘Loyal Portsmouth Garrison Company of Volunteer Infantry’ (1798) and Garrett also later played a large part as a Major in the formation of the ‘Loyal Havant Volunteers’ (1803-1809) after he moved to Leigh.

1810 - 1820

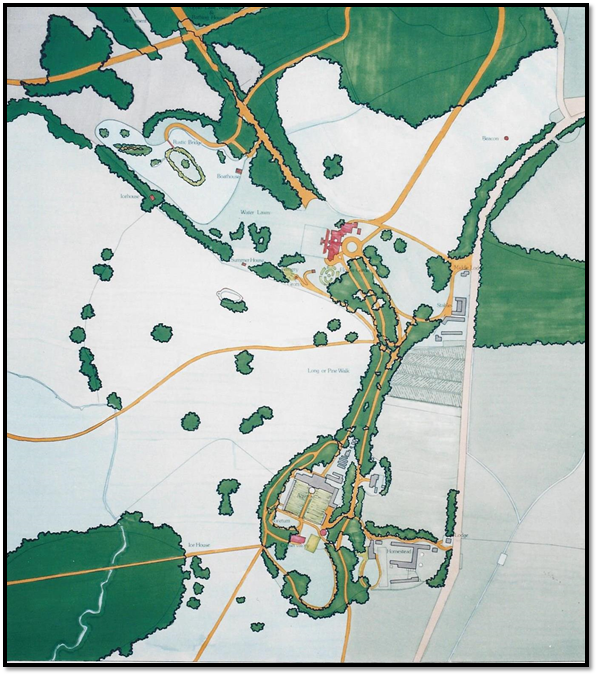

It was Garrett who played a major part in developing the estate; certainly parts of the estate bear his mark today. He landscaped the grounds and parkland around the house, fenced off the park and extended it to 400 acres; converting the farm to a ‘ferme ornee’ (ornamental farm) and laid the framework for the landscaping by Staunton that was to follow. One of his changes that still survives is the serpentine wall, also known as the ‘crinkle-crankle’ on the south side of the walled garden. By the time of the sale to Sir George Staunton in December 1819, the estate had grown in size to comprise 828 acres.

In May 1817, due to possibly family matters (his mother and unmarried sister had moved to Bath where he eventually died), Garrett negotiated the sale of the Leigh Estate to John Julius Angerstein (1735-1823). Angerstein, of Russian extraction, came to England when he was fifteen and eventually became influential in the establishing of Lloyds of London. He also became a financial advisor to William Pitt, the Prime Minister. Legend has it that Angerstein was the natural son of either the Empress Anne of Russia or Elizabeth Petrovna, the illegitimate daughter of Peter the Great. It appears that Angerstein quickly moved into Leigh House and in October 1817 even applied for permission to erect a gallery in St. Faith’s church for himself and his family. By the summer of 1818 a contract had finally been signed for the purchase of Leigh House and estate for the astronomical sum of £47,350. Unfortunately things began to go wrong; Angerstein brought a case against Garrett for not disclosing dry rot in the house. The case was heard in London in February 1819 and the charges dismissed, but Angerstein was not compelled to complete the purchase. Angerstein was an avid art collector and after his death in 1823 the Government paid £57,000 for 58 of Angerstein’s pictures and a further £3,000 for the continued tenancy of his London home in Pall Mall, so it could be opened as an art gallery. This was the beginning of what would become the National Gallery.

Unfortunately for the court case it still left Garrett with Leigh House and later in the year of 1819 he again put the estate up for sale. This time Garrett, with the aid of Chichester land agent and auctioneer Mr. Weller, had a pamphlet published of twenty ‘Letters addressed to William Garrett, Esq., Relative to the state of Leigh House ‘. This pamphlet, as well as asserting the sound condition of Leigh House has letters from twenty worthy gentry, builders and local craftsmen of the area; signatories to the letters included Rev. M.A. Norris (Rector of Warblington), Charles Longcroft, Admiral, Sir Henry Leeke of West Leigh House, Sir Samuel Clarke¬ Jervoise of Idsworth, Admiral, Sir Lucius Curtis of Gatcombe House, all stating to the sound condition of the property.

At the end of July 1819, Sir George Staunton paid his first visit to Leigh Park with the view of buying the property and was conducted around the estate by Garrett. The only disappointment that Staunton found was that the road from Havant to Horndean passed close to the front of the house, but Staunton was duly impressed enough to agree to the purchase. In September 1819 agreements were formally signed for Staunton to become the next owner of the estate and by December 1819 the deal was sealed.

1820 - 1860

Staunton’s connection with Leigh Park is well documented, suffice to say that over the next thirty years, he, with the help of the architect Lewis Vulliamy, enlarged the house and conservatories, adding the large stove house in the walled garden and adding another library – the octagonal building known as the ‘Gothic Library’ that still stands close to the walled garden. He enhanced the grounds by adding follies and temples and various garden features and created the lake, known as Leigh Water.

In 1827 he bought out-right from the Bishop of Winchester the franchise for the Manor of Havant which he inherited when he acquired the estate, and in the same year he diverted the Havant-Horndean Road that ran close to the house a further two hundred yards east, so that the road ran past the farm, the position it now occupies and not pass his front door. Under Staunton Leigh Park became one of the finest estates in Hampshire, famed for its gardens and parkland. He added plants from China, a place he knew very well from his days working for the East India Company, and plants from other parts of the world to be grown in his hot-houses, conservatories and gardens.

Sir George Staunton died at his London home on 10th August 1859 and in his will he bequeathed Leigh Park and his London home to his cousin, Captain Henry Cormick Lynch (1801-1859). The Irish estate at Clydagh, Co. Galway, inherited from his father, passed to Henry Lynch’s elder brother, George Staunton Lynch-Staunton (1798¬1882), who took the additional surname of Staunton due to the terms of the will. Unfortunately Captain Lynch died on the 22nd September, a mere six weeks after the death of Staunton. Although Captain Lynch died intestate, the estate passed to his son who also took the additional surname of Staunton by Royal Licence becoming George Lynch-Staunton. In 1860 this George Lynch Staunton (1839-1925) put the estate up for sale thus ending the forty years association with the Staunton family and Leigh Park.

The Temple of Friendship Temple ‘Parentibus et Amices defunctis sacrum’, 28 January 1830 (completed Summer 1828) by Joseph Francis Gilbert

The Temple of Friendship Temple ‘Parentibus et Amices defunctis sacrum’, 28 January 1830 (completed Summer 1828) by Joseph Francis Gilbert

1860 - 1870

At a sale in 1861 the estate was acquired by William Henry Stone, who started another exciting phase in the history of the estate. By the time of the sale to Stone the estate consisted of over one thousand acres. Stone moved to Leigh Park and within six years had demolished the Staunton mansion and erected a new house in the grounds of the park overlooking the lake. All that was left of the old house was the Gothic Library, and a large conservatory that had been attached to the house. The library still stands but the conservatory, later used as a camellia house, was later demolished.

When William Henry Stone bought Leigh Park at auction in October 1860 he was then only aged only 27 and not long out of Cambridge University. He was the son of William Stone of Dulwich Hill, London, a London merchant and staunch supporter of the Liberal Party. After a settlement was agreed, Stone paid £60,000 for the estate and moved into Leigh Park at the beginning of October 1861.

When Stone first saw Leigh Park he had reservations. The idea of the farm so close to the house did not appeal and he thought the house could be placed at a more convenient site in the grounds. It also appears that Stone was no garden enthusiast, as a huge number of Staunton’s garden features were later to disappear during his ownership.

Soon, after buying the estate, Stone employed a former University acquaintance, Richard William Drew, to design a new house for him. The place chosen was the site of Staunton’s Temple of Friendship, the highest point of the estate, with extensive views over Leigh Water towards Havant Thicket and the Forest of Bere.. Richard Drew was only a year older than Stone, and Leigh Park was one of his first major commissions. Not a prolific architect, Drew’s designs were used in other buildings in the Havant area that Stone was associated with. Notably these included the Havant Town Hall, built in 1868, and St. Faiths Church in the centre of Havant where Drew carried out work on the Tower and Chancel in 1874. Drew also designed Bedhampton School in 1868 again where Stone was an important benefactor.

The Victorian Gothic style mansion designed by Drew looked quite a lot larger than the Staunton mansion, but the dimensions were very similar in size, the principle rooms were the same size and also the number of bedrooms the same. Work started on the new mansion in early 1863. The bricks and tiles were made on site, the clay dug from pits east of Hammonds Land Copse to the north-east of the estate and fired in two kilns, which until a few years ago could still be seen in situ. Other materials were brought into the site, including chalk from Portsdown Hill and Portland stone. A building firm from Gosport, Rogers and Booth, carried out the work.

Whilst the new house was being built, Stone did not remain too inactive, he married in 1864, Melicent, the daughter of Sir Arthur Helps, of Vernon Hill House, Bishops Waltham. Sir Arthur was noted for his obituaries in the Times, writing obituaries for Prince Albert, Palmerston, Dickens, and his personal friend, Charles Kingsley, amongst others. A year later, in 1865, Stone was victorious in the election at Portsmouth, winning the seat easily as a liberal candidate after the retirement of Sir Frances Baring (afterwards Lord Northbrook).

The new house was completed at the end of 1865 and Stone and his relatively new bride moved in – the work reputably cost in the region of £20,000. After completion, the old mansion, which had stood on the site overlooking Front Lawn, was demolished. By 1868 a new entrance drive was laid and a new North Lodge had been built opposite the Staunton Arms, and slowly and surely the glories of Staunton’s age were almost disappearing. The new North Lodge still stands, clearly showing the style the new mansion took with its neo-Gothic style.

Stone carried on the tradition of Staunton, his benevolence to the people of Havant can still be found around the area, and the Stone Allotment Trust in New Lane still bears his name after his gift to the town, as does the Old Town Hall, now the Havant Arts Centre, of which he was a major benefactor. He also opened the park and gardens to the public as on one occasion; the Queens birthday on 25th May 1867, nearly 20,000 people incredibly visited the estate.

1870 - 1900

In the General Election on 4th February 1874 Stone lost his seat, trailing third of five candidates. This marked a turning point for both Stone and Leigh Park.

In October 1874, Stone decided to put Leigh Park up for sale. It would appear that a financial decision rather than losing his seat at the election was the main reason. Stone was essentially a business man, a merchant like his father, he had dealings in silk and other materials in India but it appeared that a scheme for making bricks and other clay products (a seam of blue clay was found on his father-in-law’s estate at Bishop’s Waltham) went bust nearly bankrupting Sir Arthur Helps and putting a drain on Stone’s purse. Stone had by acquiring other land (largely due to the enclosure of common land) nearly doubled the acreage of the Leigh Park estate to 1866 acres by the time of the sale in 1874. After the sale of Leigh Park Stone moved to Norbury Park, Mickleham, later moving to the aptly named Lea Park Estate, in Witley, Surrey.

The estate and the new house, which was only nine years old at the time of the sale, were bought by Lt. Gen. Sir Frederick Wellington John Fitzwygram Bt. Sir Frederick was an expert on horses and veterinary matters, and had just returned from serving with the army in India after inheriting the baronetcy on the death of his elder brother, the unmarried Sir Robert Fitzwygram. Sir Frederick, still a serving officer and later Inspector General of Cavalry and President of the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons, was fifty-one and unmarried when he bought the Leigh Park estate. In 1882 he married Angela, daughter of Thomas Nugent Vaughan and Countess Forbes and in 1884 retired from the army after over forty years service. Sir Frederick, who sat on the Havant Bench as a magistrate, was elected as Conservative M.P. in the 1884 election. He sat for the Fareham Borough of Hampshire and South Hants until his retirement from parliament in 1900.

1900 - 1935

Although there were no structural changes to the house during Sir Frederick’s residency, he carried on the tradition of Sir George Staunton, upholding the values of the gardens and parkland after what some would say their destruction under William Stone. Sir Frederick, a benevolent and well-respected figure in the neighbourhood, died aged 81 in December 1904. His only son, Frederick Loftus Fitzwygram, succeeded him in the Baronetcy as well as at Leigh Park. This Sir Frederick was only twenty when he inherited Leigh Park and set out like his father, on a military career, joining the Scots Guards in 1906. Previous to this he had studied at Oxford University. He continued to live at Leigh Park along with his mother Lady Fitzwygram and his younger sister Angela.

Sir Frederick (the fifth baronet) kept a pack of beagles at Leigh Park, and excelled at cricket, playing for Havant and captaining his own team at Leigh Park. During the Great War he served as a major in the 2nd Scots Guards, winning the M.C. and was twice wounded before being taken prisoner by the Germans in 1915. After an exchange of prisoners he was interned in Holland, where he remained until after the Armistice. During his time at Leigh Park he became one of the youngest magistrates to sit on the Bench at Havant. Sir Frederick died unmarried aged only 35 of blood poisoning and the effects of influenza at London in May 1920, but probably exacerbated by the effects of the Great War.

Sir Frederick’s mother and sister continued to live on at Leigh Park after his death, Lady Fitzwygram’s death in her 91st year in 1935 ended her 53 years in residence. In the following year Angela Fitzwygram left Leigh Park and took up residence at appropriately named Leigh Heights in Hindhead, Surrey. She died there in her 100th year in July 1984. All four members of the Fitzwygram family are buried in a family vault in the churchyard of St Michael’s, Redhill, Rowlands Castle.

1935 - present

In 1936, Miss Fitzwygram sold 1265 acres of outlying portions of the estate, this included seventeen tenanted farms, cottages and small holdings, including Middle Park Farm, Prospect Farm and Havant Farm. The majority of this land was bought by Parkleigh Investment Company who later sold a large portion of the land to Portsmouth City Council for their housing programme. The house though remained empty until the start of the Second World War, when it was taken over for a short period by Hilsea College for Girls. The Royal Navy and the Admiralty took possession of the entire site in August 1940. The house was the headquarters of HM.S. Vernon and the Superintendent of Mine Design and his staff for the duration of the war. Nissen huts were erected along the drive and Leigh Park was effectively cut off from the outside world. Secret work on the design of mines and torpedoes was carried out here and no doubt Staunton’s lake played its part in the war effort.

In 1944, Portsmouth City Council bought 1672 acres of the former Leigh Park estate, including land from Parkleigh Investment Company and other land bordering on to it, for £122,465. A further 798 acres were bought in 1946 to add to the earlier land acquired and went towards the start of what would become the building of a housing estate primarily for the bombed out people of Portsmouth. Negotiations for the sale had started back in 1943 but even before the war thoughts were in place regarding the overspill of the city. The housing estate, taking its name from the old estate, would become one of the biggest such estates in Europe. The house, park, home farm, and gardens, which numbered 150 acres, and were also bought in the sale at this time, and were to remain as a green belt area for the local people. Technically the house remained under Admiralty control until 1957 but by this time the ravages of vandalism had taken their toll and in June 1959 the decision to demolish the house was taken.

All that now remains of the house is the former terrace which overlooks the lake. The parkland, farm and gardens now form what is known as the Staunton Country Park and are preserved for future generations to enjoy.